by Lisa Hiton

Family recipes are our most precious food possessions, and yet, they are often written in longhand on a raggedy piece of paper that we revisit once or twice a year. As your family’s writer and record keeper, why not use these recipes as an entry point into writing a family food history, for generations past, present (and future) to salivate over!

When collecting family recipes, there are two things to focus on: techniques and measurements. This spring, as I prepared for Passover, I made charoset—a mixture of apples, nuts, and wine, meant to symbolize the mortar used by the Israelites to make bricks when they were slaves in Egypt, centuries ago. As I made my mixture this year, I tried to write down the measurements. I used a dozen apples to make three types of charoset. I used enough apples to fill a specific bowl. I like to mix the apples with cinnamon, red wine, toasted nuts, honey, and some secret ingredients. It is this family bowl that we use to measure. That’s difficult to pass along.

Even in trying to describe charoset, I’ve already conflated different ideas of writing about food. I’ve mentioned charoset’s symbolic meaning for the holiday, Passover; the fact that charoset is ancestral—far older than the origins of my family; a family bowl that is a unit of measurement in the recipe passed along in recent years. As you think about the foods you love, writing recipes, and reflecting on why those foods and techniques define your family, there are guiding questions you can use to organize your intuitions into a piece of writing—a family tome of recipes and their importance.

- What are your family’s favorite recipes?

- Why are they significant?

- How are the recipes recorded and passed along?

- What is the history of the recipe? In your family? Prior to your family?

- What are the feelings and memory associated with your dish and/or the ritual of making/eating it?

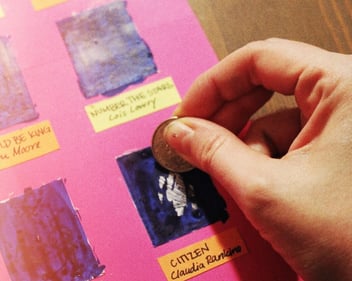

These ideas can be used to guide your documentation of family recipes, yes. Beyond just the measurements and techniques, though, you can capture and preserve an entire history of your family by writing around the recipe. By writing through it. The food—how it’s made, and later how its loved—can explicate meaning from your family, and your family can impart meaning onto the rituals of cooking and eating food. Writing those moments into your recipes can help create and archive a vibrant and complex portrait of your family history for generations to follow. So as you write down your family recipes, think of how you’d like to preserve them and how you’d like to present them to your own family. You can use illustration or photos to accompany the recipes. You might also think of how to braid the history of the recipe into the larger book of family recipes. You might even think of creating a kind of map at the opening of this collection of essays that has a key: symbols that show how your family uses unique measurements or techniques in their recipes.

Measurements

As I look through the recipes written by my elders—specifically my grandmothers—there are all kinds of shorthand notes that don’t mean much to those who’ve never cooked the recipe with them. For example, brisket is a staple item at many Jewish holiday meals. Jews in the Chicagoland area often make a savory brisket using browning sauce. On one recipe card, it simply says “browning sauce”. It doesn’t say how much, if it should be poured over the meat or vegetables, etc. My grandmother and mother both “eyeball” it. Further, they both use Kitchen Bouquet as their browning sauce—a pantry item I’ve never seen used for any other recipe in my life. These kinds of details are where you’ll need to spend time being the record keeper in your family. As you observe your family cook, keep out dry and wet measuring tools so that you can slow the process down and capture more accurate measurements.

Techniques

The most unique and valuable element in cooking a meal is the technique in which you cook. When my bubby makes apple pie from scratch, she doesn’t use any machinery besides her hands, a knife, a rolling pin. She can peel each apple in one thread. When my grandma stuffed peppers and zucchini, she hollowed them out with a specific knife. She uses a specific spoon to measure out the stuffing. When I make tzatziki, I let the garlic sit in the oil and vinegar for a long while before I mix it with the greek yogurt. Some of these techniques are more simple to qualify than others. When I watch Italian friends make pasta, they have a much clearer technique of knowing when the pasta is exactly al dente, when to add it to the sauce, and when to add a pad of butter to ensure that the sauce sticks to the perfectly textured pasta. These details can be learned, but only over time and repetition. And it is vital to record these more magical and mysterious elements of how your family cooks in order to preserve the soul of your family recipe.

With my grandma now gone, I may never get those zucchini and peppers just right, as they are in my memory. But with enough trials, repetition, and of course the key ingredient to all of the best recipes patience, I may at least land on a new version to pass on.

About Lisa

Lisa Hiton is an editorial associate at Write the World. She writes two series on our blog: The Write Place where she comments on life as a writer, and Reading like a Writer where she recommends books about writing in different genres. She’s also the interviews editor of Cosmonauts Avenue and the poetry editor of the Adroit Journal.